Proudly Sponsored by

© Copyright 2025 All rights reserved. Site Developed by Marketing Alliance, Inc.

4003 Alcorn Road Highway 552 West

Lorman, MS 39096

601-940-7206

Canemount Plantation Inn is on 40 Acres of what was Canemount Plantation dating back to the late 1700s. Many of the original buildings are still standing today.

The grounds/lawn are a park like setting with many 200 year old live oaks draped in Spanish moss. The property is surrounded by 3,500 acres of the Canemount WMA (Wildlife Management Area). We’re located 2 miles from Alcorn State University and 3 miles from Windsor Ruins.

The main house dates back to 1851 and is on the historic register. Four other buildings date back to the late 1700 to early 1800.

The six Suites are in the 1820s carriage house. They are modern rooms with hardwood floors, wool area rugs, gas fireplaces, Jacuzzi whirlpool tub/shower and wet bar.

Enjoy the outdoors under a large covered area attached to the carriage house or on the wrap around covered gallery at the main house. Also, there are tables and chaise lounges around the pool patio area.

Come and see for yourself why Windsor Ruins is the most photographed historic site in Mississippi. This magnificant architectural marvel was one of the last great homes built by enslaved Americans before the Civil War. The Ruins of Windsor must be seen in order to be absorbed into your own memory of your historic journey to Claiborne County.

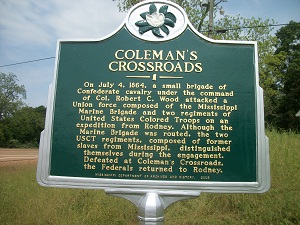

Over 17,000 African American Mississippians fought to defeat slavery in the Union Army during the Civil War. This is the site of the Battle of Coleman's Plantation in which two regiments of the United States Colored Troops of Mississippi fought Confederate troops in 1864.

As Union soldiers advanced on Port Gibson, Grant rerouted his men from Bruinsburg Road to Rodney Road, where they marched four abreast under cover of darkness, with only the sounds of the night adding to the creak of wagons and heavy treading of boots. As Sergeant Charles A. Hobbs, of the 99th Illinois described it:

The moon is shining above us and the road is romantic in the extreme. The artillery wagons rattle forward and the heavy tramp of many men gives a dull but impressive sound. In many places the road seems to end abruptly, but when we come to the place we find it turning at right angles, passing through narrow valleys, sometimes through hills, and presenting the best of opportunity to the Rebels for defense if they had but known of our purpose.

Today, Rodney Road looks a great deal as it did on that late spring evening, and though you won’t have Sergeant Hobbs as your companion, there are interpretive markers to guide you through that fateful night. Time to put on your marching boots.

On that fateful April night in 1863, the fierce fire from Grand Gulf fortifications was too hot for Union ironclads, but today you’ll find the warm welcome just right in this 400-acre park listed on the National Register of Historic Places. There are still important reminders of battle here, in the remnants of the two fortifications, Fort Cobun and Fort Wade, including a restored 1861 Parrott Rifle. There are other signs of war, too: a cemetery where Civil War soldiers are interred and a Civil War ambulance in the Grand Gulf Museum. But Grand Gulf is also an eclectic mix of other historic attractions: the historic Sacred Heart Roman Catholic Church (moved here from the town of Rodney), several historic buildings that date to the town’s founding, including the Spanish House, built in the late 1790’s, a submarine built with a Model T engine that was used to chase moonshiners in the early 20th century. Explore on foot along the park’s hiking trails, or take the birds-eye view at the top of the 75-foot observation tower that lets you look over the park and the river. You can even make your own “encampment,” but really roughing it is optional. In addition to RV and tent camping there are showers and a laundry facility nearby.

Overmatched at Port Gibson, the Confederate Army suffered casualties that included 60 killed, 340 wounded, and 387 missing out of the 8,000 men who fought that day, with 4 guns of the Botetourt, Virginia Artillery lost. (Grant’s losses were higher: 131 killed, 719 wounded and 25 missing out of 23,000 men engaged). The bodies of the Confederate dead were buried at Wintergreen Cemetery, and in 1906 the United Daughters of the Confederacy dedicated this monument, which stands in front of Claiborne County’s historic Courthouse, which was built in 1845.

It's still here! The road to Port Gibson. The sight where U. S. General Ulysses S. Grant's Vicksburg Campaign began. This is where the Union army led by General Grant, successfully crossed the Mississippi River and disembarked with the aid of intellegence provided by enslaved Mississippians. Wow! The Shaifer House is still here too! It's not hard to imagine the sound of the cadence of an army of thousands marching in formation on this wonderfully preserved raodway of Civil War history.

Built around 1845, the Bethel Presbyterian Church played an important part in spreading Presbyterianism into this part of the state, but on the afternoon of April 30, 1863, the sanctuary was a bystander as the Union vanguard passed through after landing at Bruinsburg. Some sources have reported that Union soldiers took shots at the church steeple, but there’s no evidence today, since a tornado took the entire steeple in 1943. The church is open daily.

It was just past midnight on May 1, 1863, when the two armies first clashed here at the A.K. Shaifer House. The women of the house were packing their belongings onto a wagon for retreat into Port Gibson when the first volley of the muskets rang out between the Confederate pickets of General Martin E. Green and the Union vanguard. Needless to say, the ladies wasted no more time. The pickets were also forced to fall back, as the Union army made its inexorable advance. It may have been shot in the dark for those soldiers in 1863, but the Shaifer House today is a dependably interesting stop on your Port Gibson Civil War tour. The white frame house has been carefully restored, and there are a number of interpretive signs around the property. There’s also a marker denoting that first blast—and a bullet hole still preserved in the side of the house!

1147 Ross Road

Utica, MS 39175

(601) 529-6266

www.tracetraus.net

After a day of hiking, horseback riding, and exploring the remains of a historic town, you can bed down either at one of 22 tent sites or 22 paved RV sites. (Average pull-thru and back-in size is 55'; slide-out accommodations, handicapped accessible.) Restroom facilities also available.

3026 Hwy 61 North

Port Gibson, MS

(601) 437-0993

In May of 1962, the Grand Gulf Military Monument Park was officially opened, dedicated to preserving the memory of both the town and the battle in which occurred there. Located eight miles northwest of Port Gibson, Mississippi off Highway 61, this 400 acre landmark is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and includes Fort Cobun and Fort Wade, the Grand Gulf Cemetery, a museum, campgrounds, picnic areas, hiking trails, an observation tower, and several restored buildings dating back to Grand Gulf's heyday.

Located in Port Gibson, Mississippi on Grand Gulf Road five miles north of Port Gibson, 20 miles south of WalMart in Vicksburg, MS on Hwy. 61S and 4.5 miles east of Grand Gulf Nuclear Plant. Full hook-ups offered.

Folks from all over the country sing the praises of Mr. D’s delicious fried chicken. Sometimes proprietor Arthur Davis, aka “Mr. D,” returns the favor by singing of his grandmamma. His singing is good, but the Old Country Store (which began life as a real country store in the late 1880s) really hits the high notes with down home buffet spreads.

The porch of the Isabella B&B and Restaurant—is a feast for the eyes as well as the pallet. You can't miss this beautiful Queen Anne on Highway 61 in Port Gibson. Open for lunch Monday through Friday, and dinner each evening by reservation. Stop in and you might hear a ghost story or two.

The Rosswood Mansion is a classic Greek revival home of 14 rooms, with 14 foot ceilings, 10 fireplaces, columned galleries, and a winding stairway. Completely restored and furnished with beautiful antiques and unusual items collected around the world, it has been home since 1975 for Colonel Walt Hylander and his wife Jean, who share its heritage and their treasures with their guests. Rosswood is a Mississippi Landmark, and it qualified for the National Register both historically and architecturally. It has been named "The Prettiest Place in the Country" and featured on the Travel Channel on television.

This 1880 Queen Anne home located in the heart of Port Gibson between Vicksburg and Natchez is a great stop for history buffs. Isabella opened late February of 2011 with southern hospitality and a restaurant with beverages available, including receptions, dinner parties and luncheons.

The Bernheimer House's Eclectic Architecture makes it one of the most unique homes in the US. Three stories and over 7,500 square feet makes it's the largest home in Port Gibson. Four guest rooms with private baths and a large hall and sitting area make for welcoming accomodations. The Bernheimer House's heritage dates back to the original Jewish Community that came to Port Gibson, beginning in the 1840's from Germany and France and soon became successful merchants. The Jewish Cemetary, Temple Gemiluth Chassed Synagogue, and the Drake Hill neighborhood are other examples of Jewish heritage in Port Gibson.

St. Mark's Episcopal Church

St. Mark's was organized in 1837 by Rev. James McGregor Dale and construction of the sanctuary was completed in 1855. Following the battle of Raymond on May 12, 1863, the church was used as a hospital for Federal soldiers. The interior of the church was damaged during this time, and the pews were lost. After repairs had been made, St. Mark's was consecrated by Bishop William Mercer Green on May 5, 1868.

Raymond Courthouse

Built, 1857-9, by the famous Weldon brothers with skilled slave labor crew. After the Battle of Raymond, fought 1 ¼ mi. S. W. of here, May 12, 1863, this building served as a Confederate hospital.

Confederate Cemetery

The Confederate Cemetery in Raymond contains the graves of 140 Confederate soldiers who were killed during the battle of Raymond on May 12, 1863, or who died as a result of their wounds. Most of the men were from Tennessee and Texas; many died in homes and public buildings that had been appropriated as temporary hospitals. Union dead from the battle of Raymond were initially buried here but later moved to the Vicksburg National Cemetery.

To Clinton and Jackson

On May 12, 1863, two divisions of the XVII Corps marched from the Roach Farm on the Utica Road and defeated Gregg's Confederate brigade at Raymond. The next day, McPherson's men moved to Clinton and cut the railroad. Meanwhile, two divisions of the XV Corps moved from Dillon's Farm to Mississippi Springs, five miles east of Raymond. To protect the army's rear as it pivoted toward Jackson, the XIII Corps feigned an attack on Confederate forces at Mt. Moriah, and Grant captured Jackson on May 14.

Change of Plans

On May 12, 1863, Grant made his headquarters here at Dillon's Farm with Sherman's XV Corps. At Raymond, 5 ½ miles east along Fourteenmile Creek, McPherson's XVII Corps, with 12,000 men, defeated 3,000 Confederates under John Gregg. Grant heard the guns at Raymond and at sundown learned that McPherson was victorious. Realizing that Confederate forces were now on both his left and right flanks, however, Grant changed his planned movement north and ordered the army to wheel toward Jackson.

Contested Crossing

On the morning of May 12, 1863, Grant and Sherman arrived here with two divisions of the XV Corps and found the bridge across Fourteenmile Creek ablaze. A brisk firefight ensued between a detachment of Wirt Adams' Mississippi cavalry, posted on the east side of the creek, and the 4th Iowa Cavalry. In order to drive off the Confederates, Wood's Brigade of Steele's Division and a 6-gun Union battery went into action. By 11:00 a.m., the bridgehead was secured and the XV Corps moved into position.

North to the Railroad

On May 12, 1863, after Grant and two divisions of the XV Corps marched past, three divisions of McClernand's XIII Corps turned here onto the Telegraph Road. Four miles north, they met a portion of the 1st Missouri (Dismounted) Cavalry at Whitaker's Ford. After the Confederates fell back, the Federals secured the ford. Meanwhile, McClernand's reserve division captured Montgomery Bridge over Fourteenmile Creek, 2 ½ miles west of Whitaker's Ford, securing Grant's left flank 4 ½ miles from the railroad.

Old Auburn

On May 11, 1863, two division of Sherman's XV Corps camped here. Water was scarce, and Sherman reported to Grant that he was "short of provisions and ammunition" while captured mail indicated "many million rations in Vicksburg." The next morning, Grant rode from Cayuga and joined Sherman for the move toward the railroad. The XIII Corps left Fivemile Creek, 1 ½ miles southwest, at 5:30 a.m., following the XV Corps. McPherson's men from the XVII Corps were at the Roach Farm, 6 miles southeast, and marched toward Raymond.

Final Plans at Cayuga

Grant established his headquarters here on May 10, 1863, remaining two days. On May 11, Tuttle's and Steele's divisions of the XV Corps passed through Cayuga and the XIII Corps camps at Fivemile Creek to Auburn, 3½ miles northeast. McPherson's XVII Corps, suffering from lack of water, marched only 1½ miles from Weeks Farm to the Roach Farm. Grant pressed McPherson to move into Raymond advising that “we must fight the enemy before our rations fail,” and notified Washington that he would no longer be in communication.

Historic Crossroads

On May 9, two divisions of McPherson's XVII Corps marched to Reganton, then known as Crossroads, and moved southeast toward Utica, camping at Meyer's Farm three miles southeast. On May 10, the XIII Corps marched through here from Big Sand Creek toward Cayuga and Fivemile Creek. Steele's division of the XV Corps moved to Big Sand Creek, while Tuttle's division remained at Rocky Springs. McPherson moved past Utica and camped at the Weeks Farm. Grant moved his headquarters from Rocky Springs to Cayuga.

Concentration of Troops

On May 7-9, 1863, three divisions of the XIII Corps camped here, while a reserve division was at Little Sand Creek, two miles southwest. On May 8, Grant reviewed the troops here. On May 9, the XVII Corps marched through Reganton and turned toward Utica. After they had passed, the reserve division moved here. One of Sherman's XV Corps divisions marched to Rocky Springs while another remained at Hankinson's Ferry. By the end of May 9, Grant had concentrated more than 35,000 men within five miles of Rocky Springs.

To the Railroad

On May 8, 1863, as the Union XV Corps left Grand Gulf, two divisions of the XVII Corps rested at Hankinson's Ferry and Rocky Springs to wait for rations. Three divisions of the XIII Corps camped at Big Sand Creek, 1 ½ miles northeast, while a fourth was at Little Sand Creek. On May 9, the two XVII Corps divisions marched through here along the Natchez Trace and passed through the XIII Corps divisions, which remained in camp. The object of these maneuvers was to move the army toward the Southern Railroad.

Federals Occupy Rocky Springs

After U.S. Grant had planned much of his campaign at Mrs. Bagnell's, 4 miles west, he arrived at Rocky Springs with Logan's division on May 7, 1863. He remained until May 10, allowing Sherman's XV Corps to cross the Mississippi and rejoin the army. McClernand's XIII Corps arrived here on May 6, and moved to Little Sand Creek, 1 ½ miles northeast, and Big Sand Creek, 3 miles northeast, on May 7. Grant issued motivational orders to his troops at Rocky Springs and reviewed McClernand's men at Big Sand Creek on May 8.

Grant at Hankinson's Ferry

After occupying Willow Springs on May 3, 1863, Gen. U.S. Grant divided his force. The XVII Corps advanced on Hankinson's Ferry 5 miles north of here in two columns. Gen. M. M. Crocker's division driving up this road encountered a Confederate roadblock held by Col. F. M. Cockrell's Missourians on Kennison Creek. After a spirited clash in which Crocker was compelled to use 5,000 troops, the Rebels fell back. Covered by Cockrell's stand, the Confederate army had retired across the Big Black. The 20th Ohio reached Hankinson's Ferry just as the Rebel engineers were preparing to destroy the flatboat-bridge. While Capt. S. De Golyer's Union guns roared, the Ohioans charged over the bridge, scattering the Confederates. Possession of the bridge enabled Grant to send patrols across the Big Black and up the Vicksburg road. Such thrusts helped confuse the Confederate leaders about Federal intentions. The XVII Corps camped in the fields south of the river from May 3-7. From May 4-7 Grant's headquarters were at Hankinson's Ferry.

Fight for Hankinson's Ferry

As Logan's division marched west toward Grand Gulf on May 3, 1863, M.M Crocker's division moved toward Hankinson's Ferry. At Kennison Creek, one mile north, the road was blocked by two Confederate brigades. After a spirited skirmish, the Confederates fell back across the Big Black River. On May 4, Grant established his headquarters at Mrs. Bagnell's 3½ miles north, and sent reconnaissance forces toward Vicksburg and Jackson. On May 6, Grant decided to move northeast toward the railroad east of Vicksburg.

Skirmish at Willow Springs

When Union Gen. J. B. McPherson's XVII Corps reached Grindstone Ford, 2 miles south of here at dusk on May 2, 1863, the troops found the bridge across Big Bayou Pierre burning. Col. J. H. Wilson and a detachment put out the fire. During the night the Federals repaired the bridge.

Col. A. E. Reynolds' Mississippians reached Willow Springs during the night, took position on the bluffs overlooking the bottom, and waited for the Yankees to cross the river. Gen. J. A. Logan's division spearheaded the Union advance on May 3. Confederate artillery opened as the bluecoats scaled the escarpment, forcing Logan to halt and deploy. Seeing he was terribly outnumbered Reynolds pulled back and set up a roadblock at Ingraham's plantation ½ mile northeast of here, where he was reinforced. Pushing on, the Federals, after a spirited clash, drove the Rebels from Ingraham's and back toward Hankinson's Ferry.

While Gen. U. S. Grant regrouped his army and waited for Gen. W. T. Sherman's arrival, troops of McClernand's XIII Corps camped here from May 3 to 7. Union foragers visited the neighboring plantation, seizing food and supplies.

The Road to Vicksburg

On the afternoon of May 3, 1863, Union Gen. U.S. Grant rode west past this intersection to Grand Gulf while Gen. John A. Logan's division turned north toward Vicksburg. Logan was in pursuit of the Confederate force which had abandoned Grand Gulf early that morning. In the early hours of May 4, Grant returned here from Grand Gulf and joined his troops near Hankinson's Ferry, where Logan had captured a raft bridge over the Big Black River, opening the road to Vicksburg.

After Grant had crossed the Mississippi River unopposed on April 30, 1863 and had won the Battle of Port Gibson on May 1, the victorious Federals marched into Port Gibson the following day. In his memoirs Grant succinctly stated his next objective, "My first problem was to capture Grand Gulf to use as a base." But the Confederates had destroyed the two bridges where the centuries-old Natchez Trace crossed two rivers, Little and Big Bayou Pierre. As a result, Union pioneers were required to toil for twenty-two hours on these bridges, but at 5:30 a.m. on Sunday morning, May 3, Grant moved rapidly and pushed his troops over the second water barrier, Big Bayou Pierre, using the charred but recently-repaired bridge at Grindstone Ford.

Grant's crossing of Big Bayou Pierre meant that the Grand Gulf Confederate garrison, if it were still there, was caught in a cul-de-sac formed by the Mississippi, Big Bayou Pierre, and Big Black Rivers. Grant realized this and peeled Maj. Gen. John Logan's division west from Willow Springs toward Grand Gulf to snag the prey, then hurried Brig. Gen. Marcellus Crocker's division north from Willow Springs toward Hankinson's Ferry on the Big Black to seal the only way out. Preceding Logan's infantry column on the road to Grand Gulf was a company of Ohio cavalry, and here, at a sharp curve four and one-half miles west of Willow Springs, the troopers ran headlong into a Confederate brigade.

The savvy Confederate Brig. Gen. John Bowen had positioned Missouri infantry and artillery here to protect the intersection of the Grand Gulf-Hankinson's Ferry road while he evacuated his garrison from Grand Gulf. Confederate Corp. Ephraim M. Anderson of the 2nd Missouri Infantry wrote, “We had been in line probably an hour, when the strokes of horses’ hoofs and the rattle of sabers were heard coming down, and the head of a regiment of Federal cavalry soon made its appearance in the turn of the road, a hundred yards distant . . . The artillery opened upon it about the same time that [the infantry], from the shrubbery in front, fired a volley into its ranks.” The Northern horsemen, after rounding the curve and being treated to a peppering of Southern canister and bullets, quickly fell back toward Willow Springs. Around 2 p.m. Logan's infantry column arrived to brush aside the pesky Rebels, but all that his men found were a few stragglers from a retreating column and an intersection littered with the jetsam of war. But this intersection was key, because from this obscure junction Grand Gulf was only seven miles to the west, and Hankinson's Ferry was only nine miles to the northeast. From Hankinson's it was only sixteen miles to Vicksburg.

Reports rippled down the column and soon Grant rode to the front and glanced downward at the thousands of footprints in the dust. The fresh signs of travel toward the ferry told his experienced eyes that Grand Gulf had been evacuated only hours before. Orders were snapped to Logan to pursue the fleeing Rebels, and Col. Manning F. Force of the 20th Ohio recalled that the troops "made a sharp turn and pushed for the ferry." Grant, however, continued straight ahead to Grand Gulf with a score of cavalrymen for protection. Governor Richard Yates of Illinois rode with Grant and recalled, "I saw guns scattered along the road, which the enemy had left in their retreat . . . I consider Vicksburg as ours in only a short time, and the Mississippi River as destined to be open from its source to its mouth." His words were prophetic. Grand Gulf was the back door to Vicksburg, and its abandonment had left that door open.

On to Vicksburg

After crossing the Mississippi River and fighting the battle of Port Gibson on April 30–May 1, 1863, Gen. U.S. Grant moved to capture Grand Gulf as a base of operations against Port Hudson, Louisiana. Capturing Grand Gulf on May 3, Grant learned that Union forces under Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks were not yet in position at Port Hudson, and decided to move against Vicksburg instead. Grand Gulf then became Grant's forward supply base and by May 8 over 2,000,000 rations were stockpiled here for Grant's army.

From here, on May 3, 1863, Grant caught his first glimpse of four of Admiral David D. Porter’s ironclad gunboats and was pleased to see that the US Navy occupied the site of the burned-out town. The Confederate fortifications of Grand Gulf were now in Union hands and Grant finally had his critical base “on dry ground on the same side of the river with the enemy.” Here he could amass the necessary ammunition and food to support his army. Grant wrote, “When I reached Grand Gulf on May 3 I had not been with my baggage since the 27th of April and consequently had no change of underclothing, no meal except such as I could pick up sometimes at other headquarters, and no tent to cover me. The first thing I did was get a bath, borrow some fresh underclothing from one of the naval officers and get a good meal on the flagship (USS Louisville) . . . About twelve o’clock at night I was through with my work and started for Hankinson’s ferry, arriving there before daylight.”

Turn right at the marker and follow the “Grant’s March” directional signs along the Grand Gulf-Raymond Scenic Byway.

This historic road was used for generations to haul cotton from the Rocky Springs area to Grand Gulf for shipping south to the Gulf of Mexico and to Europe, Africa, and South America. In early May 1863 it was used by Grant’s quartermasters to transport ammunition, coffee, salt pork, and hardtack to the troops as they marched deep into Mississippi’s interior.

Grant having attended to every conceivable detail aboard Louisville, mounted up at midnight for the fourteen-mile ride to join McPherson's two divisions near Hankinson’s ferry on the Big Black River. Grant's late night ride to Hankinson's must have bewildered his staff officers, for in addition to the late hour, the entourage followed a route that Lt. Col James H. Wilson, who rode with Grant that night, described as a "strange and circuitous road." In contrast, a few hours later, Sylvanus Cadwallader, a newspaper reporter for the Chicago Times, traveled this same route and wrote; “Soon after daylight on Monday morning [May 4] I mounted a captured mule, with such equipment as could be hastily obtained, and took the road leading by way of Hankinson’s ferry to Vicksburg. The ride, notwithstanding the annoying peculiarities of an illy broken mule, was one of the most delightful of my life. It was a well traveled thoroughfare, along elevated ridges, through dense forests (sometime for miles) of large magnolias, then in full bloom; or through thickets of black haw, and wild plums, along the creeks and small brooks which I frequently crossed, past acres and acres of mayflowers (mandrake) also in bloom, and by Virginia rail fence at every plantation presenting an impenetrable hedgerow of sassafras and wild grapevines. The grass was growing luxuriantly, birds were singing joyously, and everything seemed to be putting on the beautiful garments of springtime. The fragrance of bud, blossom and flower became absolutely oppressive, until the forenoon sun had partially dissipated it. Occasional stragglers and slightly wounded men pushing ahead in pairs and squads to rejoin their commands were the only human beings I encountered for several hours.”

A few days later on May 8, Lt. Charles D. Miller of the 76th Ohio Infantry, a regiment in Maj. Gen. Sherman’s 15th Corps, marched out of Grand Gulf along this road. The lieutenant recalled: “We remained at Grand Gulf for one day and then marched eastward, following the south bank of the Big Black River. Our line of march was over roads winding between low round clay hills. We passed through magnolia forests which were in bloom. The grand white flowers and shining green leaves of the trees festooned with grey moss presented a beautiful appearance. Flocks of parakeets flew screaming over our heads.” Lt. Miller was describing the Carolina parakeet, a small green parrot with a brilliant yellow head, reddish orange face and pale beak, an extinct species which lived here in the old-growth forests along the Mississippi. The bird was tragically wiped out in the late 19th and early 20th centuries due to deforestation and hunting for their colorful feathers.

Grand Gulf

The town of Grand Gulf was burned by Admiral David Farragut's men in 1862 and occupied by Porter's Mississippi Squadron on May 3, 1863. The Union occupation followed Confederate Brig. Gen. John Bowen's evacuation of the town after the battle of Port Gibson on May 1. Gen. U.S. Grant visited here on May 3, and established Grand Gulf as the primary Union supply depot for the duration of the Vicksburg Campaign. From Grand Gulf, some 200 wagons per day were used to resupply Grant's army.

Stand on the porch of the old country store and face directly across the open field in front of the store, then look to your left at the old Mississippi River bed behind the fishing camp.

On May 3, 1863, Maj. Gen. Ulysses Grant and a score of federal cavalrymen descended the steep watershed of the Mississippi River where the historic road enters Grand Gulf on the far side of the square. The mounted party arrived at Grand Gulf just before dark, and Grant could barely discern the phantom-like forms of four of Admiral David D. Porter's menacing black ironclad gunboats, Louisville, Carondelet, Mound City, and Tuscumbia, which were lined up along the muddy river bank like gargantuan snapping turtles.

Now that Grant was in Grand Gulf, per his agreement with General in Chief Henry W. Halleck in Washington he was to send troops south to Port Hudson "to cooperate with General [Nathaniel P.] Banks in the reduction of that place." But Grant wanted no part of such a plan, and had said that, "Once at Grand Gulf I do not feel a doubt of success in the entire driving out of the enemy from the banks of the river." Grant also knew that Banks was a slow-moving political general, and he was painfully aware that the former Massachusetts governor had seniority over him. But a solution to this conundrum was produced when Grant boarded flagship Louisville. It was a message from Banks, dated April 10 and written in Brashear City (today Morgan City), Louisiana. Banks wrote that his forces "could not be at Port Hudson before the 10th of May, and then with only 15,000 men." This was the loophole that Grant had hoped for and he seized the opportunity. "The news from Banks forced upon me a different plan of campaign from the one intended," he rationalized.

That night Grant sent a message to Washington saying, "I shall not bring my troops into this place, but immediately follow the enemy . . . until Vicksburg is in our possession." Grant knew that a major Northern victory was long past due and that the time for that victory was short. A large segment of the northern populace had grown war-weary, and peace Democrats, or "Copperheads," clamored for a negotiated end to the war. President Abraham Lincoln needed to counter the peace demand with good news from the front, and what better news than the capture of Vicksburg and the opening of the Mississippi River ? Years later Grant said, "I felt that the Union depended upon the administration, and the administration upon victory . . . Unless we did something there was no knowing what, in its despair, the country might not do." So Grant puffed his omnipresent cigar and made his momentous decision to move fast, strike hard, and finish rapidly.

Grant later said that his message to Washington would take "some time to reach Cairo (Illinois) by boat, and some time for response ‒ eight days I think." He also knew that the cautious Halleck would never agree to the bold new plan. "I remember how anxiously I counted the time I had to spare before that response could come," Grant recalled in an 1878 interview. Then he quipped, "You can do a great deal in eight days."

After deciding to go after Vicksburg on his own, Grant carefully made plans to establish his new supply base at Grand Gulf. While back in Louisiana on April 30, Grant had assigned one of his aides, Col. William S. Hillyer, to be his new logistics czar with the responsibility of "superintending the transportation and supplies to the army below Grand Gulf." Now that Grant was in possession of Grand Gulf, he placed Hillyer in command of the base. Grant then sent orders to Brig. Gen. Jeremiah Sullivan, in command of the troops protecting the army line of communications in Louisiana, and assigned him the task of building a road from Young's Point, Louisiana to a point on the Mississippi River nine miles below Vicksburg. Such a road would shorten the vulnerable land transportation road from forty to ten miles. Grant then wrote to his 15th Corps commander, Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman, who was protecting the army's vital Milliken's Bend supply base near Vicksburg. Sherman was to have Maj. Gen. Frank Blair's division escort 120 loaded supply wagons southward to Grand Gulf. Grant punctuated his order to Sherman by reminding him "of the overwhelming importance of celerity." He also pronounced to a skeptical Sherman that the enemy was "badly beaten, greatly demoralized, and exhausted of ammunition." Grant concluded with, "The road to Vicksburg is open. All we want now are men, ammunition, and hard bread." Since Blair's departure would practically denude Milliken's Bend of troops, Grant then wrote to Maj. Gen. Stephen A. Hurlbut, commander of the 16th Corps in Memphis, and ordered him to send four regiments by steamboats to replace Blair's men. Finally, Grant wrote to his wife to assure her that both he and their twelve-year-old son, Fred, who was accompanying his father during the campaign, were fine, and to say that he felt proud of his army.

All seemed to be in order, except that, despite Grant's encouragement, Sherman remained pessimistic. Sherman had written to his wife on April 29, prophesying that, "when they take Grand Gulf they have the elephant by the tail . . . my own opinion is that this whole plan of attack on Vicksburg will fail, must fail." But, even with Sherman's dire predictions, in a few days Col. Hillyer had the old town square of Grand Gulf piled high with crates containing nearly two million rations. Grant, the former logistician, was not about to "disregard his base" as was reported to Washington the next morning by tag-along Assistant Secretary of War Charles A. Dana.